We’re bringing you exclusive content from our newsletter, The Forecast, right here on Medium. Sign up for our newsletter here. This story is from our feature called the Weather Corner, where we take a deep dive into weird weather around the world, from our February 19th, 2021, newsletter.

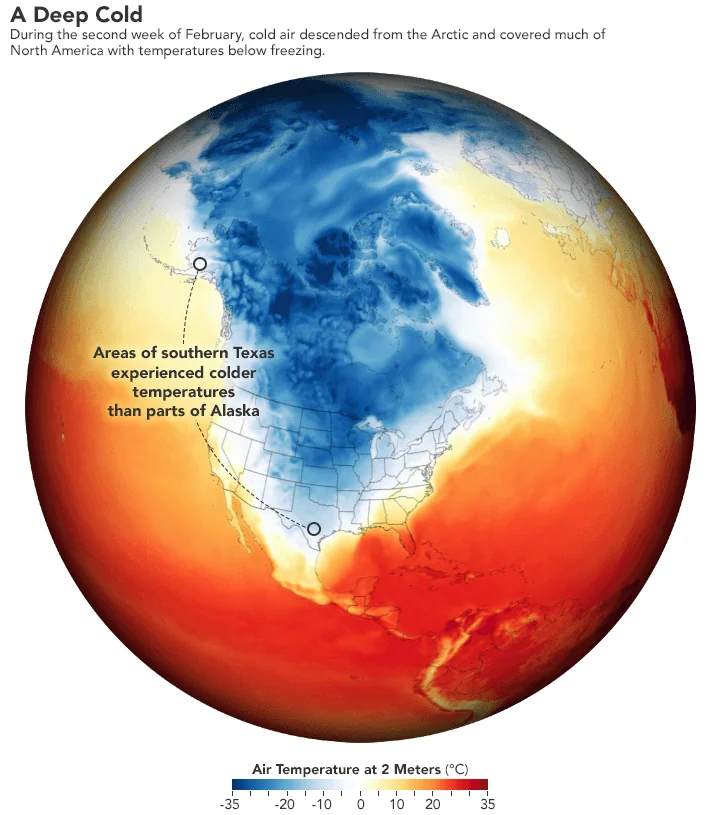

As you probably have already read, this week, serious winter storms tore through the American South and Great Plains leaving more than 23 people dead and many more injured from the unrelenting assault on parts of the country that rarely experience severe winter weather like this.

In addition, the storms caused millions of Americans to lose power and running water as temperatures dropped to record levels — some of whom are still without it. There are reports of people dying from exposure, from slip-and-falls, car crashes, and amid the power outages, from carbon monoxide poisoning and fires as they seek alternative heating sources because the electricity they rely on has been off for more than four days.

There were even reports of a “snownado” over a frozen Texas lake: essentially, waterspouts — a rotating column of air that forms over water — of snow and ice that form over either frozen lakes or snow-covered areas.

To take a step back, let’s understand how this storm is happening and why it’s unusual. We described it in last week’s Weather Corner (If you recall our explanation of the polar vortex, feel free to skip ahead). The breakdown:

A split polar vortex is bearing down on the Northern Hemisphere, bringing frigid temperatures and extreme precipitation along with it. Behind the catchy name is a serious weather phenomenon that will affect everyday life in much of the world for weeks and even months to come. You might remember the polar vortex making an appearance in the news in 2019, when Chicago briefly became colder than the North Pole, or the cold snap in East Asia in 2016, when at least 85 people in Taiwan died from hypothermia and cardiac arrest.

So what exactly is a polar vortex? Technically, it’s a unique type of low-pressure system: it’s the large area of frigid air, spinning at a high atmospheric altitude, above the North Pole. The spinning winds form a jet stream. When strong and intact, the jet stream bottles in the cold air above the Arctic, and North America has a generally mild winter.

A polar vortex actually forms every year — the result of polar night, the all-winter dark spell in the Far North. Without sunlight, the air drops to 195 degrees Kelvin (78.15 degrees Celsius, or -108.67 degrees Fahrenheit) and the winds pick up. It vanishes once spring returns, only to re-form around September or October.

However, sometimes, in the dead of winter, warmer air infiltrates and weakens the vortex. It pushes the jet stream further to the south. This brings the frigid air, plus stormy weather and increased snow chances, further south, too …

If you think you’ve heard about the polar vortex more frequently in recent years, that’s because you have. While the phenomenon is well-documented, scientists say that its behavior has become more extreme as a result of climate change. Global temperatures are rising, but the Arctic is warming more than twice as quickly than the global surface average. It’s a negative feedback loop: high temperatures have melted a great deal of Arctic sea ice, changing the icy surface that reflects light to a dark surface that absorbs it and warms.

This effect weakens and destabilizes the polar jet stream more often, causing it to dip and carry polar air farther south in never-before-seen ways.

Well, now these never-before-seen ways are here. In Texas, for example, the situation is unprecedented: The deep freeze this week caused power demand to skyrocket as residents tried to heat their homes. At the same time, a large fraction of natural gas and coal-fired power plants have been knocked offline by the low temperatures and icy conditions, due to the water facilities that these power plants need to run freezing in the cold temperatures or losing access to the electricity they require to operate. Many of these plants don’t have the infrastructure set up to operate in cold like this, so they’re not producing power.

Plus, Texas’ grid is unique in that it’s the only state that has a deregulated and decentralized electric grid. That means that when things are business-as-usual, Texas can’t easily export excess power to neighboring states. But amid the ongoing outages, it can’t easily import power either.

The state has had damaging cold snaps in 2011 and 2018. But this week’s storms caused record-low temperatures, plus unusual snow and ice — pushing the grid to its breaking point.

It’s not only Texas. More than 73% of the mainland US was covered by snow Tuesday, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office of Water Prediction — the largest area covered by snow since such records started in 2003.

Extreme weather is accelerating due to climate change, and impacts like the ones that Texas is experiencing will become increasingly common.

As the New York Times writes:

[quote text=”“The crisis sounded an alarm for power systems throughout the country. Electric grids can be engineered to handle a wide range of severe conditions — as long as grid operators can reliably predict the dangers ahead. But as climate change accelerates, many electric grids will face extreme weather events that go far beyond the historical conditions those systems were designed for, putting them at risk of catastrophic failure.“]

These impacts haven’t just been relegated to the U.S. — they have had international implications. The cold weather’s impacts have extended beyond into Mexico, where ClimateAi’s own engineer Edgar Rojas lives.

[quote text=”“You would think that Texas freezing over has nothing to do with the northern states of Mexico, but it turns out that natural gas is imported from Texas to generate electricity in Mexico,” Edgar said. “So this caused a shortage which made northern states lose power, affecting our Monterrey-based team. What also came as a surprise on Monday, was that the government decided to cut power to other states in Mexico to compensate for this deficit, so even though I live near the south-central region of the country, my power was also cut. They didn’t give us any type of warning — power was just cut so we had to stop working on features that were planned. Thankfully, our power generation has been normalized, and our engineering team can continue working as planned.“]

Creating more resilient infrastructure, from roads to electric grids, could help avert the worst impact. For electric grids, measures such as fortifying power plants against extreme weather, setting up microgrids, and installing more backup power sources are clearly critical, but will certainly prove expensive.