We’re bringing you exclusive content from our newsletter, The Forecast, right here on Medium. Sign up for our newsletter here. This story is from our feature called the Weather Corner, where we take a deep dive into weird weather around the world, from our March 3rd, 2021, newsletter.

This week, we’re bringing you a deep dive into extreme weather right here in ClimateAi’s own backyard: California.

California and the American West at large frequently make headlines for the extreme weather we experience, from droughts to heat waves to wildfires to landslides.

Right now, the majority of California is staring down moderate to severe drought conditions, according to the state’s drought monitor.

The precipitation so far is only 30% to 70% of what the state would expect to have seen during a normal year, according to the Guardian. What’s worse, these conditions follow an extremely dry water year last year (the U.S. Geological Survey defines a “water year” as the 12-month period between October 1st and September 30th of the following year, so we’re talking about October 2019-September 2020).

Source: Drought.gov

Usually, California has a wet season from November through February, when historically the biggest weather systems in Northern California cause high rain and snow totals. But the beginning of this water year, since October, has already been one of the driest on record. That doesn’t necessarily mean that the rest of the year won’t be wetter — California has one of the most variable climates of any U.S. state, often seeing very wet years followed by extremely dry ones.

Still, if this lack of precipitation continues into the year, it will become a part of a concerning trend: a multi-year drought. That would mark the third multi-year drought in the past 15 years (2006–2009, 2011–2019, and 2020-?). Multi-year droughts are especially dangerous because the impacts of the drought compound each year: resources available continue to decrease, economic reserves become depleted, and environmental stress levels increase.

Expected precipitation in the form of rain, and snowfall in higher elevations in the state, refills reservoirs, packs away snow for spring runoff to feed drier parts of the state, and helps stem the risk of wildfires. It also allows California’s agriculture sector to continue producing important crops.

California’s rainy season has been shrinking due to global warming changing atmospheric conditions. A recent study found that the state’s wet season is beginning nearly a month later than it did in the 1960s and that the autumn season has become progressively drier, largely due to climate change. This, combined with average temperatures going up in California, especially in late summer and early fall, California is vulnerable to more frequent and worse wildfires: Fires are burning hotter, faster and more intensely as heat turns vegetation into dry tinder.

All of this puts the state’s agriculture at risk. Over a third of vegetables and two-thirds of the fruits and nuts in the entire U.S. are grown in California. The state accounts for over 13% of the nation’s total agricultural value.

Image source: The OC Register

Modern agriculture in the state began in the 1920s, when farmers began transforming the desert in the middle of the state, known as Central Valley, into verdant crop fields by pumping groundwater to the surface in the 1920s. In the 1970s, California undertook a massive water infrastructure project to deliver water from wetter parts of the state to the Central Valley and elsewhere, relieving some of their reliance on groundwater. Currently, the state irrigates more than 9 million acres of cropland using roughly 34 million acre-feet of water diverted from rivers, lakes, and reservoirs that brings this water through an extensive network of aqueducts and canals. But it’s not enough anymore.

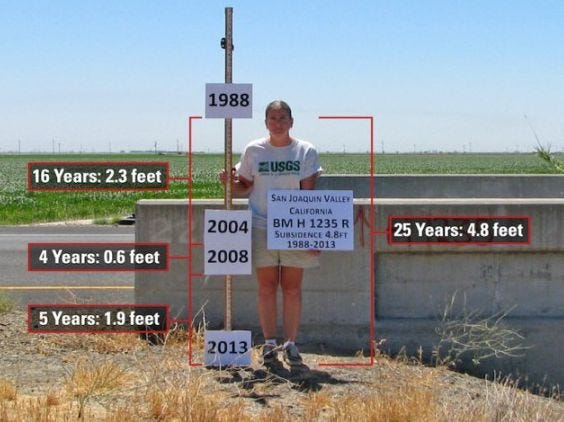

When these rivers, lakes, and reservoirs aren’t replenished and the state’s agricultural regions enter a drought — which is all happening more frequently, as described above — growers again face net water shortages. They resort back to pumping groundwater, drilling deep underground to pump water from aquifers in order to grow crops and water landscaping (this practice is largely unregulated in the state, so landowners are allowed to pump “reasonable” amounts of groundwater on their property). However, this groundwater depletion leads to the thousands of miles of land sinking.

Source: Interesting Engineers

Even still, in severe droughts, farmers can’t get enough water to operate at full capacity. From 2014–2016, when the state saw the worst drought conditions in records kept for 120 years, almost 1 million of California’s 27 million acres of cropland were left unplanted. This primarily impacted Central Valley farmers, who mostly grow field crops like cotton and alfalfa for livestock forage. With climate change’s continued impacts on the frequency and intensity of precipitation, heat waves, and other extreme events, Californian farmers will continue to see situations like this.

Take barley, for example. Most California barley is grown in the Central Valley as an irrigated rotation crop, and in the foothills and south Central Coast area as a rainfed crop. Barley yield increases with more water availability, and decreases with extreme temperatures. Therefore, the future impacts of climate change — rising temperatures, leading to lower water availability — will likely negatively impact barley yields in the coming decades.

The ‘worst case’ scenario would be devastating for barley. Xie et al/Nature Plants

California is responding to its droughts (and by extension, climate change) by passing legislation. In 2015, amid the severe multi-year drought, the state made long-overdue groundwater and sustainable water investments. Many localities implemented water conservation plans, and the federal government provided millions in emergency grants to drought-stricken communities and farmers.

Water resources will define how the world mitigates and adapts to the impacts of climate change. Conservation programs, smart agricultural production planning, climate-intelligent crop breeding, and improved water use can help tackle some of these key water risks. A sustainable agriculture system that addresses water will allow us to protect against extremes and adapt to the unavoidable at the same time.

Have any more questions about global weather events, their impacts, and how they’re linked to climate change? Send them to media@climate.ai — we will choose one to answer in the next newsletter.