We’re bringing you exclusive content from our newsletter, The Forecast, right here on Medium. Sign up here. This story is from our feature called the Weather Corner, where we take a deep dive into weird weather around the world, from our July 14th, 2021, newsletter.

As the heat in the Western U.S. and Canada that we covered last newsletter continues, we’re going to talk about another reason that heatwaves (and global warming at large) can be so dangerous to people: a measurement called the “wet-bulb temperature.”

It’s a measurement of more than just how warm the air is — it measures how hot it feels to humans. It’s even more accurate to human perception than the more well-known heat index, which also takes into account the temperature and the relative humidity.

The wet bulb temperature is specifically designed to measure the stress on a human body from the heat. When heat and humidity reach a certain point, the body can’t cool itself down with its natural cooling mechanisms.

(In particular, humans typically stay cool by sweating, because sweat droplets form on skin, then evaporate in the heat and cool the skin, bringing down body temperature. However, if the air is not dry enough to take up moisture — once the relative humidity surpasses 95% — then the sweat can’t evaporate, and humans overheat.)

Meteorologists literally measure wet-bulb temperatures by wrapping a wet wick around the bulb of a thermometer. At 100% relative humidity, the wet-bulb temperature is equal to the air temperature (dry-bulb temperature); at lower humidity the wet-bulb temperature is lower than dry-bulb temperature because of evaporative cooling.

So how high is too high? A wet bulb temperature of 35 degrees Celsius (95 degrees Fahrenheit) can be fatal after a few hours, even with ideal conditions such as unlimited drinking water, inactivity, or shade, so in practice, wet bulb temperatures would be much lower. (That’s theoretically equivalent to a heat index of 70 degrees Celsius (160 degrees Fahrenheit)).

The ongoing heatwave across the Western U.S. and Canada are getting close to these unsurvivable temperatures. The Californian desert, aptly named Death Valley, hit 54 degrees Celsius (130 degrees Fahrenheit) multiple times over the last month. It also had the planet’s hottest 24 hours on record Sunday, July 11: Its temperature, averaged over day and night, was an unprecedented 118.1 degrees Fahrenheit.

Hourly maximum temperature at Death Valley National Park’s Furnace Creek Visitor Center July 6–12, 2021. Image credit: NOAA.

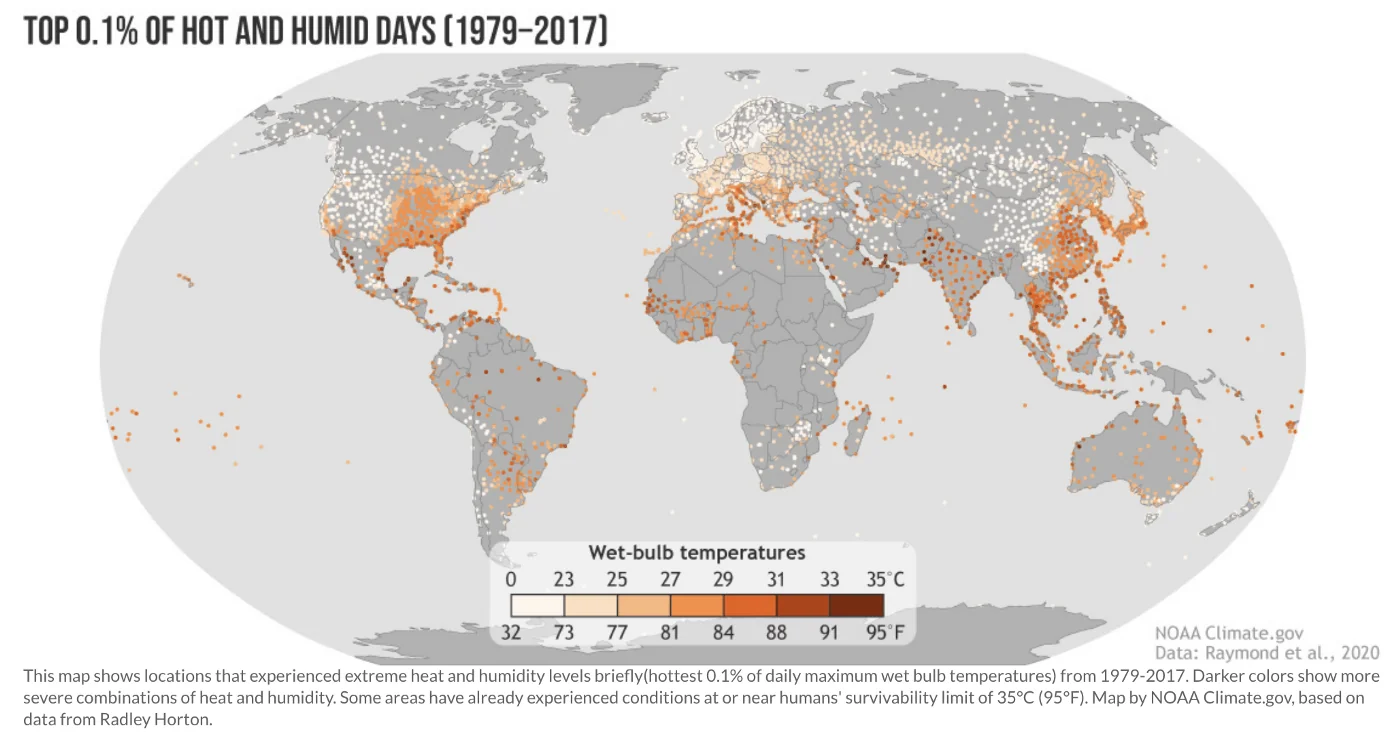

The coastal Middle East is also experiencing some of the worst wet bulb heat in the world — earlier this month, five countries hit temperatures above those seen in the western U.S. and Canada. Other parts of the U.S. are seeing rising wet-bulb temperatures too: Southeastern states have reported multiple incidences of wet-bulb temperatures at or above 88 degrees in recent years. Parts of Arizona and California have reported wet bulb temperatures as high as 95 degrees in the past, according to NOAA.

The world hasn’t reached 35 degrees Celsius wet bulb temperatures yet, but climate scientists say that with more warming, they could. Studies indicate that wetbulb temperatures could regularly cross 35°C if we pass the 2 degrees Celsius warming limit set out in the Paris climate agreement in 2015, with The Persian Gulf, South Asia and North China Plain on the frontline of deadly humid heat. These hot spots were primarily concentrated in coastal areas near high ocean surface temperatures and intense continental heat — a recipe for dangerously hot and humid conditions.

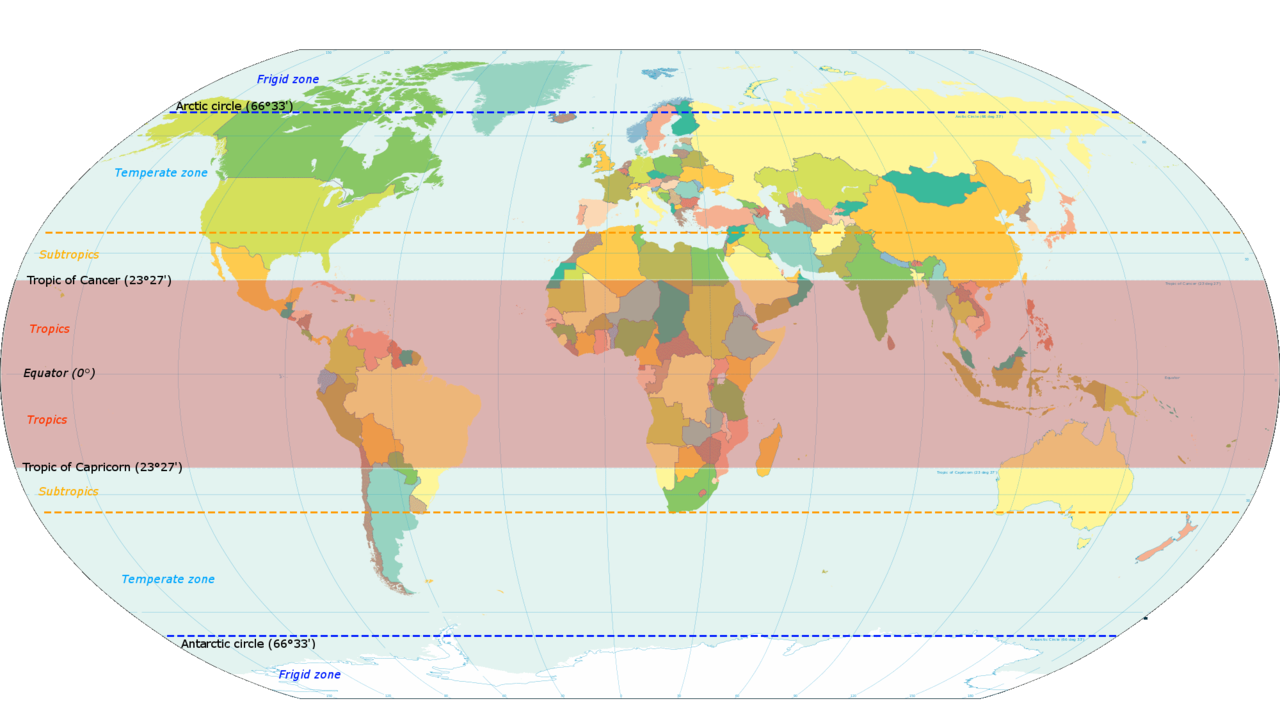

Still, wet bulb temperatures could render parts of the world like the tropics unlivable overall. Parts of the world near the equator could become too hot and humid for human survival if global warming isn’t curbed, according to a Princeton University study published this year in the journal Nature Geoscience. It focused on tropical regions between 20 degrees latitude north and 20 degrees latitude south, already some of the hottest places on Earth.

The researchers concluded that wet-bulb temperatures will continue to rise unless global warming is limited to 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit above pre-industrial levels, the desired goal of the Paris Agreement.

“If this limit is breached, infrastructure like cool-air shelters are absolutely necessary for human survival,” Mojtaba Sadegh, an expert in climate risks at Boise State University who was not involved in the research, told the Guardian. “Given that much of the impacted area consists of low-income countries, providing the required infrastructure will be challenging.”

These regions produce major fruits, such as banana and plantain, citrus, coconut, mango, and pineapple. They also grow specialty crops like tea, cocoa, and coffee. Many kinds of maize and rice are grown there, and livestock is also raised.

To combat these disastrous effects, more investment and planning are needed: early warning systems, dramatically expanded cooling centers, and forecasts featuring wet-bulb temperatures, especially when it comes to heatwaves. Governments also need to rebuild infrastructure, energy infrastructure particularly, to make it resilient in the face of new climate extremes; retrofitting homes and “future-proofing” agriculture by developing new strains of crops that can thrive.